Month Ten in Málaga – Of Poets and the Spanish Civil War

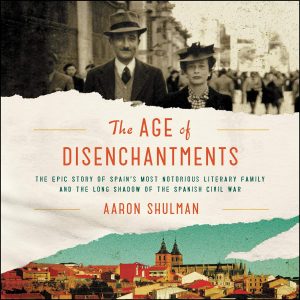

Can one be enchanted by a book titled The Age of Disenchantments?

I don’t remember what led me to this book, that is, what led me to the story of the poet Leopoldo Panero, but whoa, am I glad I encountered it because it riveted me. The prologue begins with the death of Federico García Lorca on a moonless night, an irony given how the moon was a motif in so much of Lorca’s poetry. It’s a preview of the ironies and oppositions that abound in the story of Panero, his wife Felicidad, and their three “brilliant and troubled sons”—Juan Luis, Leopoldo María, and Michi—all of whom were writers and whose lives and works are viewed as a reflection of Spanish society and history before, during, and after the Franco dictatorship.

In 2012 Aaron Shulman, an American living in Spain, was invited by a friend to view a documentary, saying “Lo vas a flipar” (You’re going to love it.). Shulman indeed loved seeing El Desencanto by Jaime Chávarri, released in 1976, the year after Franco’s death, and his resultant obsession with this family led him to write The Age of Disenchantments. The story begins with Leopoldo Panero who was born in 1909 to a well-off family in Astorga in the north of Spain, enjoyed a happy and privileged childhood, and as a young man pursued his passion for poetry while embracing left-wing causes and then, inspired by a visit by Peruvian poet and avowed communist César Vallejos, veering toward Marxism. But with the advent of the Spanish Civil War when Nationalists gained control of the north and Leopoldo’s survival was in question, Shulman writes, “It seemed there was only one realistic option left for Leopoldo. To become a fascist.”

In 2012 Aaron Shulman, an American living in Spain, was invited by a friend to view a documentary, saying “Lo vas a flipar” (You’re going to love it.). Shulman indeed loved seeing El Desencanto by Jaime Chávarri, released in 1976, the year after Franco’s death, and his resultant obsession with this family led him to write The Age of Disenchantments. The story begins with Leopoldo Panero who was born in 1909 to a well-off family in Astorga in the north of Spain, enjoyed a happy and privileged childhood, and as a young man pursued his passion for poetry while embracing left-wing causes and then, inspired by a visit by Peruvian poet and avowed communist César Vallejos, veering toward Marxism. But with the advent of the Spanish Civil War when Nationalists gained control of the north and Leopoldo’s survival was in question, Shulman writes, “It seemed there was only one realistic option left for Leopoldo. To become a fascist.”

So he did, eventually becoming the unofficial poet laureate of the Franco years and writing a book of self-righteous verses with venom for Pablo Neruda (whose “visceral anti-fascism” was “born in the blood-soaked streets of Madrid”) and jingoistic praise for Spain.

There is the question of what the legacy is of a poet who trades his beliefs for his desire and his human right to exist when other poets fought and died for the Republic and others fought from exile with their words. That legacy is explored both in Chávarri’s documentary film and in Shulman’s book. It’s a legacy to which Felicidad and the three sons contributed, were complicit in, and tried to salvage. Shulman describes the family as being trapped “between two dueling urges: the desire to create and to destroy.”

What they created survives in many forms.

“The Paneros were prolific creators. During the 105 years of their existence, from Leopoldo’s birth in 1909 to Leopoldo Maria’s death in 2014, they wrote several thousand pages of poetry and prose.”

The family house in Astorga, at which El Desencanto was filmed, is now a museum. It’s on my list of destinations in Spain.

A plaque commemorates the building where the Panero family lived in Madrid. On a recent trip to the capital, I crossed the Retiro from my hostel on Gran Via to find it. Here’s an article in Spanish by Javier Mendoza, stepson to Michi Panero, and his reaction when he first set foot in the apartment at Calle Ibiza 35.

And here in Málaga, Leopoldo Panero’s papers are archived in El Centro Cultural Generación del 27.

The Spanish Civil War, as wars are, was brutal, each side committing horrors such that in order to move on to a democracy after Franco’s death, the government passed the Pact of Forgetting in which both the left and the right agreed to “leave the atrocities in the past.”

There is a reluctance among Spaniards to discuss the civil war among themselves because of the deep divisions it caused among friends, neighbors, and families. But would they speak to an outsider about the dictatorship? I decided to ask the one Spaniard I have become friends with who lives just outside of Madrid. He happens to be my age which means he was born during the dictatorship and experienced the transition to democracy when he was in his early twenties. I extracted this summary of a snippet of a slice of an hour-long, recorded interview, whose complete transcription and translation will have to wait for another time.

Claudio acknowledged that a lot of people recall the dictatorship with bitterness. He is not one of them. He was born and grew up in the countryside. His father had been in the war but never fired a shot, while an uncle was wounded in the battle at Zaragoza and soon after fled to France, never to return to Spain. There wasn’t much talk about the dictatorship or the war in his house. He was adamant that he never felt any lack of liberty or safety, though he did describe how his father would listen to a radio program that originated in France only after locking the doors, closing the windows, and smothering the radio turned low with a blanket. Still, Claudio is firm in his declaration that he felt safer during the dictatorship than he has since the transition to democracy in terms of vulnerability to crime. This is a sentiment I also heard from a forty-seven-year-old Malagueño I met an at intercambio who described what he knew of his parents’ views. Could it be related to that convenient lack of due process in a dictatorship? At any rate, I’m grateful to Claudio for his time and to anyone else who is willing to talk to me about— really, anything.

Spanish Acquisition Report

To meet the challenge of speaking and finding ways to practice and have meaningful exchanges with people in Spanish, I recently made a couple of conversation dates.

With Miguel, who is half-Dutch and half Spanish, (his mother is from Soria where Antonio Machado taught and where he met and married his child-bride—see my December post), our conversation revolved around history and literature and la movida madrileña—the post-Franco countercultural movement that had its beginnings in El Pentagrama, a bar in the Madrid’s Malaseña neighborhood. I took a photo of it on a recent trip to Madrid. Miguel is also an eclectic reader and recommends books by Juan Madrid, Arturo Pérez-Reverte, and Camilo José Cela. I noted the lack of women on his list, so I recommended that he read Maria de Lourdes Victoria.

With Miguel, who is half-Dutch and half Spanish, (his mother is from Soria where Antonio Machado taught and where he met and married his child-bride—see my December post), our conversation revolved around history and literature and la movida madrileña—the post-Franco countercultural movement that had its beginnings in El Pentagrama, a bar in the Madrid’s Malaseña neighborhood. I took a photo of it on a recent trip to Madrid. Miguel is also an eclectic reader and recommends books by Juan Madrid, Arturo Pérez-Reverte, and Camilo José Cela. I noted the lack of women on his list, so I recommended that he read Maria de Lourdes Victoria.

Karlo is from Croatia and is spending the academic year at the University of Malaga as a teaching assistant through the Erasmus program. A student of languages, his Spanish is fluent, and he reads a half-dozen languages. His thesis is a comparison of the use of the subjunctive across Spanish, Italian, French, and Portuguese. (I know!) Our conversations cover a lot of ground, including books. Here is a list of Croatian authors Karlo recommends:

Cyclops by Ranko Marinkovic

The Bridge on the Drina by Ivo Andric

Dark Mother Earth by Kristian Novak

Croatian Tales of Long Ago by Ivana Brlic-Mazuranic

Where are all the Spanish language learners who want to discuss books? I responded to a Meet-up opportunity organized by a local Spanish teacher for Spanish language learners wanting to talk about books. I was the only one who signed up, so I enjoyed a full hour of one-on-one literary conversation in Spanish. It was a stars-aligned moment because the sentences seemed to flow from me, though with the spigot turned low.

People come, people go

This is a line from the 1932 movie Grand Hotel in which one of the characters observes, People come, people go. Nothing ever changes, when in fact the movie is filled with characters with interesting stories.

This is how I view the writers group I attend weekly. Attendance varies since many participants are in Málaga for short stays of three months or less, others move elsewhere by choice or because of employment. The shifting make-up is both interesting for the opportunity to continually meet new people but it’s also sad to see people whose company you’ve enjoyed and valued leave. Here’s a photo of the group this week. We already miss Miguel who moves to Madrid this weekend for a new job.

You are unearthing fascinating stories that lead to finding even more!

Your friend’s remark about feeling “safer” under the dictatorship brought to mind remarks made by an elderly Russian friend who lives in Moscow and said she feels the same way. Today the appeal of the “strong man” has returned in some countries, but the Spanish electorate has rejected a return to the past and that gives me hope!

Yes, stories abound here and so often they’re right in front of me. But they also lead me to other cities, which is exciting. And it will be interesting to watch Spanish politics over the next few years and into the next election regarding the influence of the right.

Your Miguel reminds me of what happened in Argentina. We still have people feeling nostalgic about the military dictatorship of the seventies, when more than 30,000 people were killed or disappeared. We are so glad that democracy prevailed in the end (even now, with the new authoritarian president, democracy is functioning!).

I think you’re referring to Claudio, but, yes, despite the brutality of a dictatorship, there are many who find merits in it.

Wonderful to hear your stories, Donna, of your new home. I’m fascinated by your curiosity and the places it takes you. I’m re-learning Spanish via Duolingo after a visit to Mexico. Es muy interesante y divertido!

Yes, there’s a lot of wonderful stuff to learn and I love it when I can hear first-hand experiences. Suerte en el aprendizaje del español!

A recent NYer has a memoir by John Lee anderson about his early days as a wanderer. Some people must continually be on the move.

Found the article! Will read it!

Donna, this post touches me soul in so many ways! First of all, thank you for recommending my writing, it is such an honor for you know how much I admire you as a writer, reader, human being. Me encanta que estés en España perfeccionando tu español! When I read your posts I feel like buying a ticket and moving to Spain right now. This week I shall look up the book and the documentary you mention. The subject of the Spanish Civil War is fascinating, and it can be dangerous as it has trapped plenty of writers (like me) into devoting years of their lives to try to understand it. And of course there are no easy answers, just pain. A lot of pain :((( Muchas, muchas gracias amiga por mencionarme, por compartir tu maravillosa pluma, y por ser mi amiga. Eres una bendición más en mi vida. No dejes de escribir nunca.

Maria, siempre me inspiras. Sería genial si compraras un billete para mudarte a España. O al menos ven a visitarme. También me fascina la Guerra Civil Española y lo que siguieron—la dictadura, la transición, la movida madrileña—y lo que estaban pasando en los artes. Con placer sugerí tus libros a Miguel. Él me dio que seguramente va a leer uno. Él mismo ha escrito una novela negra que tiene lugar durante la movida madrileña, pero no está publicado. Te echo de menos y espero que nos veamos algún día en España. Ha ha, I’m getting brave about posting in Spanish. I hope there are not too many errors porque siempre hay. Gracias por tu amistad, Maria.