Some Things I Read and Did in 2019 – A Mash-up

This past year I read good books and experienced good things. Here are a few of each of them matched up in a semi-random, teeny bit calculated way, introduced by a few lines from the featured book.

From “1989” in How to Write an Autobiographical Novel, a deeply perceptive and intelligent collection of essays by Alexander Chee:

Everyone is running now and everywhere batons rise. The screams lift out of the street, and in restaurants up and down the block doors are locked and the diners are informed.

Everyone is running now and everywhere batons rise. The screams lift out of the street, and in restaurants up and down the block doors are locked and the diners are informed.

In “1989,” Chee writes about the AIDS march in San Francisco and the response of the riot police to the disruption of traffic. It’s a short, powerful essay about his realization that the police were directing their brutality not just at the people who were protesting, but at what they were fighting for – all of this happening in the country he lived in.

I read this essay months before I went to Ecuador, landing during street protests in Quito where students, workers, and indigenous activists were tear-gassed by police and military units. This was not my country, but I sided with the people and their demands for social and economic justice.

From The Friend by Sigrid Nunez, which won the 2018 National Nook Award for Fiction:

Rather than write about what you know, you told us, write about what you see. Assume that you know very little and that you’ll never know much until you learn how to see. Keep a notebook to record things that you see, for example when you’re out in the street.

Rather than write about what you know, you told us, write about what you see. Assume that you know very little and that you’ll never know much until you learn how to see. Keep a notebook to record things that you see, for example when you’re out in the street.

I read this beautiful book on our flight to Spain in May. A woman grieving the death of her lifelong best friend recalls the above advice from him. I’ve never been good about keeping a journal or recording thoughts and observations in a notebook. But during the three weeks we were in Spain, at the end of each day I logged our activities, typing them into my phone, including this incident in Segovia: We arrived at the tiny Casa-Museo Antonio Machado to find it closed during the siesta hours. On the step outside sat two middle-aged men, one of them reciting poetry in beautiful, lilting tones, and the other listening, nodding. I missed out on seeing the museum, but I was grateful to have witnessed that.

From “As Luck Would Have It” in Staten Island Stories by Claire Jimenez, an engaging collection I reviewed for Seattle Review of Books:

One day Chrissy had the bright idea to reach out to the ghosts. She thought that perhaps we could make peace with them if only we could all just sit down and talk.

One day Chrissy had the bright idea to reach out to the ghosts. She thought that perhaps we could make peace with them if only we could all just sit down and talk.

I believe in ghosts and I fear seeing strange ones, that is, the ghosts of people I haven’t known. But I welcome the ghosts of beloveds. If not their ghosts, then their living, breathing doubles. One hot Sunday afternoon in February, while I was walking down a nearly empty street in Oaxaca, an elderly woman was walking toward me. There was something familiar about her dress, her shoes, her pace. I prepared to greet her as we neared each other. I can’t remember if I managed to extend a “buenos dias” to her. I don’t even remember if she looked my way or if she was focused on the gently upward slope of the sidewalk ahead of her. But as soon as she passed me, I stopped immediately and whirled around to watch her walk away, resisting the urge to rudely catch up to her for another look at her face, which eerily resembled my long-dead Mexican grandmother.

From The Vexations by Caitlin Horrocks, a smart and enthralling fictional account of the life of composer Eric Satie:

“You a writer?” a man asked, glancing at Philippe’s notebook. The man was wearing a jacket, not a smock, and his collar was gray and crooked. He made a strange tinkling sound as he leaned over the bar, as if he were strung with wind chimes. His nose was a nearly bloody-looking red, and his eyes were already glazed.

“You a writer?” a man asked, glancing at Philippe’s notebook. The man was wearing a jacket, not a smock, and his collar was gray and crooked. He made a strange tinkling sound as he leaned over the bar, as if he were strung with wind chimes. His nose was a nearly bloody-looking red, and his eyes were already glazed.

Still, Philippe thought this was possibly the best single thing anyone had said to him in his life. “Yes,” he said. “Yes, I’m a writer. What are you?

“A drunk,” the barman said, refusing to serve the man the absinthe he’d requested.

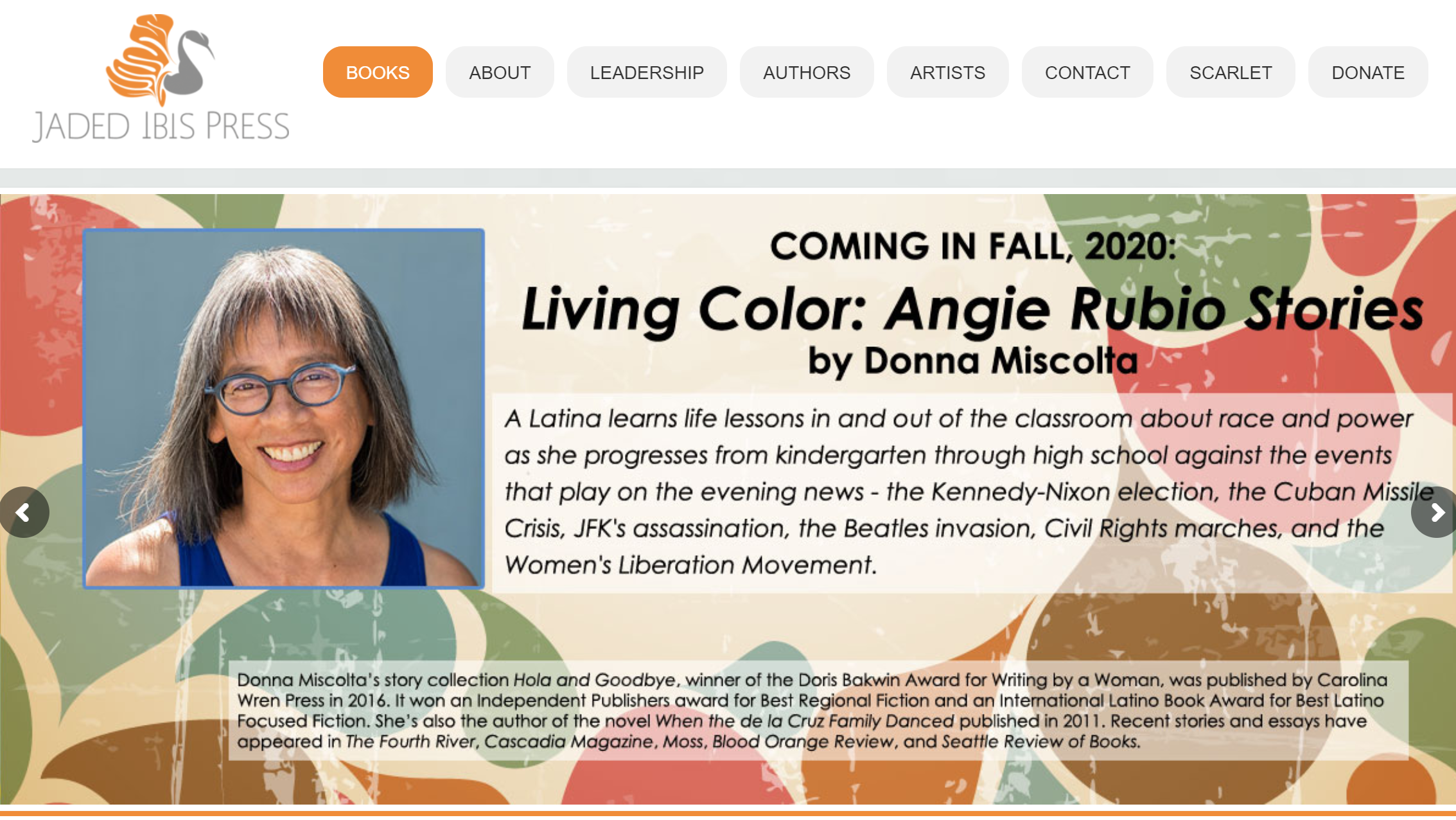

This novel, rich in character and setting, includes among its themes art and genius versus art and talent and the ever-constant doubt that accompanies both. The passage above features Phillippe, who comes to Paris from Spain and encounters obstacles in trying to make his name as a poet. Imposter syndrome is real for writers. Even when we feel confident that the work we’ve finished is good and deserving of publication, once we send it out into the world seeking a publisher, we are beset with doubt that anyone will find it worthy. So, it was with gladness and relief that I learned in late May that Jaded Ibis Press will release my third book of fiction Living Color: Angie Rubio Stories in fall 2020.

From Hezada! I Miss You by Erin Pringle (forthcoming March 2020), a beautiful novel about the change, loss, nostalgia, and memory that accompanies a dying circus and the dying village it visits:

The tumblers run up the street and jump high into the splits. When they land, they raise their arms to applause, then take off again, running, jumping, now twisting too many times to count before they land facing the other side of the street. More applause. They rise up on their toes, arch their backs, and reach as though to touch the sky, defiant at the rain.

The tumblers run up the street and jump high into the splits. When they land, they raise their arms to applause, then take off again, running, jumping, now twisting too many times to count before they land facing the other side of the street. More applause. They rise up on their toes, arch their backs, and reach as though to touch the sky, defiant at the rain.

Who doesn’t love performers? They are deserving of our applause. Especially improv actors. Last April the multi-faceted Jekeva Phillips invited me to participate in BIbliophilia. My part was easy: I read an excerpt from one of my Angie Rubio stories. Then, in one of the most creative acts I’d ever witnessed, a group of improv actors took over where I left off. After a brief huddle, the actors took the stage and continued my story in spontaneous and incredibly funny, smart, and seamless dialogue and action. Like an ice sculpture that melts or a sand painting that is erased, that performance was a one-time thing – unscripted, unrecorded, never to exist again. I suppose that’s the point of improv – its ephemeral nature, its beauty and power. But how I wish I could’ve wrapped that performance up and taken it home with me to watch again and again.

From The Body Papers by Grace Talusan, an exquisitely crafted memoir about trauma, identity, and family:

Inside a few cells in my brain, I believe there’s a part of me that still knows Tagalog. I feel pain when I attempt to speak it, as though there is something I want to say desperately that can be expressed only in my first language. But I can’t access words, or that part of me that named the world first in Tagalog. When I hear strangers speaking Filipino languages, I am as drawn to them as kin.

Inside a few cells in my brain, I believe there’s a part of me that still knows Tagalog. I feel pain when I attempt to speak it, as though there is something I want to say desperately that can be expressed only in my first language. But I can’t access words, or that part of me that named the world first in Tagalog. When I hear strangers speaking Filipino languages, I am as drawn to them as kin.

I have a similar response to Spanish, though I have never spoken it fluently. It’s a language that I heard throughout my childhood and one that I feel connected to despite my failure to exit from intermediate purgatory in my speaking level. At least my desire for connection through the English language is met through community with other writers through readings, conferences, and retreats. Among the opportunities I had this year was participating on panels at the Orcas Island Literary Festival and teaching at the Hedgebrook Summer Salon. Both times I had the pleasure of hanging out with writers I admire who are also exceptional human beings.

From The Importance of Being Wilde at Heart by R. Zamora Linmark (which I reviewed for Seattle Review of Books), a YA novel about first love, which centers the thoughts, desires, and concerns of gay, trans, and gender-fluid teens:

He closes his eyes. He lies there, very still, and with his shaven head, he looks like a newborn baby who wakes up to greet the world, then returns back to sleep.

He closes his eyes. He lies there, very still, and with his shaven head, he looks like a newborn baby who wakes up to greet the world, then returns back to sleep.

These are the protagonist’s observations about the boy he falls in love with. Linmark’s reference to a newborn gives the moment innocence and intimacy because we understand the purity of that moment when a baby wakes up and the tenderness of falling back into slumber. I have a grandson now to remind me of the hope we feel when we behold this innocence. I saw him in the first hours after his birth, sleeping in all his newness. I saw him open his eyes to a world still small to him. Now every time he opens his eyes, his world increases and his awareness of himself in it increases. As he grows, he will always have the support of those who love him to be whoever he wants and needs to be in this world that is big and often beautiful, but not always welcoming.