Portal to My Grandmother

Writers write because they have an affinity, even a compulsion, for words. We love and are driven to make sentences that grow into stories that touch the reader in some way. It’s how we communicate. And even though making sentences might require much hair-pulling and brow-furrowing, we trust that the words, sentences, and clarity of intent will eventually come to us – like old friends or a loyal puppy.

But what happens when you try to learn another language? When you try to communicate in it? When you know the words on paper and understand them when you hear them out loud, but they vanish somewhere between your head and your tongue when you try to speak them? When you feel completely useless trying to summon them from the far reaches of your brain where they have burrowed themselves like gusanos in the maguey or where they have drifted in a stew of conjugations, past with present, future with conditional, the subjunctive deliberately hiding itself among the others – not a single friend or loyal puppy in the mix.

I’d heard Spanish frequently while growing up. My grandmother who immigrated from  Mexico in 1924 never learned English. My mother and her siblings could speak Spanish to varying degrees, but I grew up feeling that it wasn’t my language to know, or worse, that I wasn’t capable of knowing it. It meant I would never really know my grandmother.

Mexico in 1924 never learned English. My mother and her siblings could speak Spanish to varying degrees, but I grew up feeling that it wasn’t my language to know, or worse, that I wasn’t capable of knowing it. It meant I would never really know my grandmother.

Over the years, I’ve made multiple attempts at learning Spanish, but the gap between brain and tongue always yawned big and wide. Maybe a couple of weeks of immersion would trigger latent synapses in my cerebral cortex. I’d been listening to Spanish language podcasts for months before my trip to Oaxaca and the Spanish Immersion Program there. Surely, once I arrived in Mexico, magic would happen and the soup inside my head would bubble itself into something coherent and fluent, and the language of my grandmother would finally be mine too.

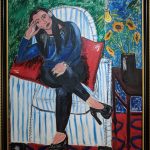

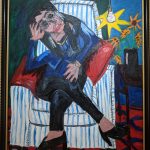

Instead, I became a Victor Hugo Pérez painting. Before my first class, I went to the Museo de Pintores Oaxaqueños. Two paintings by Pérez seemed to foretell how I would perform on that first day of classes. I felt like everything I’d ever known about Spanish had suddenly (switching metaphors here) melted like a box of crayons in the sun.

My five hours a day of instruction were split into two-and-half-hour blocks, with theoretically the first class devoted to grammar and the second to conversation. In fact, both sections were built heavily around conversation. My teachers knew English, some a lot, others just a little, but we only spoke Spanish. Mine was halting and full of errors. I ended up working with four teachers during my two weeks of classes, which exposed me to different manners of speaking, styles of teaching, and personal interests. From Miriam, I learned a little about the Zapotec people and language. Reina was a terrific source of information about the history and culture of Oaxaca. Ruben and I had a fun discussion about names, and the one afternoon the delightful Valeria was my teacher, she made a game of the subjunctive. All were smart and highly competent teachers and were fun to be around.

- Miriam

- Reina

- Rubén

- Valeria

There were definitely times that I felt that the immersion thing was working. So, if you’re looking for a recommendation, I give mine wholeheartedly and if I were to give it in Spanish, I would use the subjunctive form as in Les recomiendo que inscriban en Spanish Immersion Program. Or I would command you to do so with the imperative form as in ¡Inscribanse!

Sometimes my ploy was to ask my teachers questions about themselves or about Oaxaca, or even just about a point of grammar so I could just listen and not think so much about constructing sentences of my own. Other times, especially during the second week, there was a genuine give-and-take of conversation.

I was doing other things to ensure my immersion. After my first week of classes I participated in the Intercambio at the Oaxaca Lending Library where I spent an hour in fairly effortless Spanish conversation with a young Oaxacan. When I took tours, I opted for  the Spanish-language guides. When I met up with the artist Fulgencio Lazo, who resides in both Seattle and Oaxaca, we spoke Spanish over an evening meal. And vivacious Martha, my homestay host, was always ready to engage in conversation and gently correct errors.

the Spanish-language guides. When I met up with the artist Fulgencio Lazo, who resides in both Seattle and Oaxaca, we spoke Spanish over an evening meal. And vivacious Martha, my homestay host, was always ready to engage in conversation and gently correct errors.

But then classes ended. Suddenly without the daily lessons and practice, not to mention my teachers who had reduced their normal rate of speech to facilitate my comprehension, I felt once again as if the language was escaping me, that what I had learned and practiced over the last two weeks had assumed its favorite resting state of deliquescence.

The Sunday after classes ended, I went to Fulgencio’s house for desayuno. His brothers, sisters-in-law, and some friends were there. It was a lovely and lively group of people. It was also the first time I’d really sat at a table amidst multiple Spanish speakers with different styles and rates of delivery. While I could follow the conversation, there was absolutely no way I could contribute anything to it. I was so focused on listening to and decoding their words, I had no capacity to produce any of my own. After that morning, I felt again as if becoming fluent in Spanish was out of the grasp of my aging brain and increasingly less agile tongue.

Later that day when I was hot, tired, and hungry, I went for some abarrotes at the tienda a few blocks from where I was staying. I was jolted when I passed an old woman whose face and demeanor reminded me of my grandmother, a woman who’d never had a deep or reflective conversation with her grandchildren because they couldn’t speak Spanish. I turned around to watch the woman make her way up the hill as if I were really watching my own grandmother move slowly away from me. It’s far too late for me to learn Spanish to speak to her, but I don’t want it to be too late for me to honor her by learning her language. So, I’ll keep trying. Voy a continuar. Sí, voy a hacerlo.

Thank you for sharing your journey! To study the language of our ancestors wakes something up in our hearts, even if the pronunciation isn’t perfect. Continua y hacer! <3

Gracias, Gabriela!

Very interesting Donna and so relatable for me as well. My mother and her immediate family were all form El Salvador. I grew up in the Bay Area hearing Spanish spoken in my home daily. But also felt that it was “not my language to know.” Sadly now I wish I were bilingual. I think my mother felt that I was an American and did not need her language. She could easily spoke Spanish to me in the home and I would have learned English in school. I took Spanish in college thinking some latent knowledge would work its magic and I would easily get a good grade. No such luck. Dissecting sentences is a whole different world. Also, the instructor was from Spain and her dialect of Spanish was very different from my mothers, my aunts and grandmother. Good for you for trying! Very brave. Best, Tina

Thank you, Tina!

Donna, I am sure you have made great progress. You actually understood conversation at a dinner table!!? Amazing. It takes much much longer to produce your own words, as when a baby learns. I love your commitment and your reason for learning this beautiful second language. Annual holidays in Mexico are hereby prescribed 🙂

Thanks, Rachel! I am going to try to go to Mexico every year!