Life in Málaga—Mujeres

I belong to a group of women that meets every couple of weeks to converse mainly in Spanish. Diana, the group’s originator, is the only one that is fully bilingual having been raised in a Spanish-speaking family and spending part of her life in Colombia. The rest of us can claim functional bilingualism since we’ve all been in situations with doctors, realtors, or home repair people where we’ve had to explain, expound upon, and sometimes debate using whatever vocabulary lived in the forefront of our brain in the moment.

At a recent meeting we gathered at Diana’s to watch a movie called La virgen roja. It’s set during the Second Spanish Republic, those fleeting years of liberalism before the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. The story is about Hildegart Rodriguez who was raised by her fiercely feminist mother to be a prodigy of socialist thought, feminism, and sexual liberation. In raising Hildegart, the mother is strict, unforgiving, and possessive. Her specific intent is to mold the ideal independent woman that will inspire future generations to copy her masterpiece. Aside from being a feminist, Hildegart’s mother was a eugenicist. A mad scientist. One with a lofty goal but mad, nonetheless.

At a recent meeting we gathered at Diana’s to watch a movie called La virgen roja. It’s set during the Second Spanish Republic, those fleeting years of liberalism before the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. The story is about Hildegart Rodriguez who was raised by her fiercely feminist mother to be a prodigy of socialist thought, feminism, and sexual liberation. In raising Hildegart, the mother is strict, unforgiving, and possessive. Her specific intent is to mold the ideal independent woman that will inspire future generations to copy her masterpiece. Aside from being a feminist, Hildegart’s mother was a eugenicist. A mad scientist. One with a lofty goal but mad, nonetheless.

I won’t spill the habichuelas, but let’s just say the story doesn’t end well for the young, precociously intellectual Hildegart or for her Dr. Frankenstein of a mother for that matter.

As feminists we were simultaneously engaged and aghast. Yet, we were glad to have found out about her to add to our growing knowledge of Spanish history, particularly as it relates to the contributions of women.

For the subsequent meeting we each agreed to research a significant woman in Málaga history and deliver in Spanish a short presentation about her. We met at Fiona’s for lunch for a gorgeous platter of roasted vegetables and gammon, “the cured hind leg of pork primarily used in British/Irish cuisine” (Thanks, Wikipedia.) I failed to get a picture of this beautiful, aromatic, delicious dish. This was followed by a Lancashire bomb, a creamy, tasty ball of cheese encased in black wax, accompanied by crackers, chutney, and sliced kiwi. To top it all off was an apple crumble and fresh fruit. There was also white wine and a bit of rosé in the mix, not to mention tea.

Photo public domain

Once we stuffed our faces, we got down to the business of speaking Spanish and sharing what we had learned about famous Spanish women. Diana started us off but not with a Malagueña. She went big picture and royally so with a report about Victoria Eugenia (called Ena), the granddaughter of Queen Victoria who married Alfonso XII, the King of Spain whose grandson Juan Carlos helped engineer the transition to democracy after the Franco years. Ena’s grandson is Felipe, the current King of Spain. While her husband Alfonso was occupying himself with having affairs and blaming her for bearing two hemophiliac sons and one deaf one, Ena dedicated herself to improving conditions for women, children, and the poor, and helped reorganize the Spanish Red Cross. When Ena married Alfonso, she had to learn Spanish, which she did very quickly, and she also converted to Catholicism though she had a low regard for Spanish religious conservatism. She hated bullfights and collected fine jewelry, some of which has been passed down through subsequent generations and on occasion is worn by the current queen. This is a rapid summary that doesn’t do justice to an interesting woman who never quite felt at home in Spain.

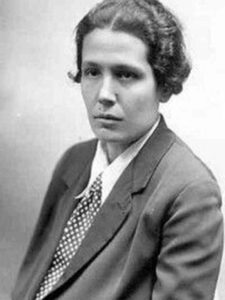

Photo from Women’s Legacy website

Next Rita told us about the life of Victoria Kent, born in Málaga in 1897. She became an attorney and later a member of parliament in the Second Spanish Republic. She was soon after named Director of Prisons where she worked on reform. Notably she was opposed to suffrage for women believing that Spanish women had been too much influenced by the Church to be responsible and independent voters. With the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Kent went into exile in Paris. After the war, she was tried in absentia by the Franco government and sentenced to 30 years in prison. Protected by a false identity she remained in France until 1948 when she exiled in Mexico and soon after the United States where she was hired by the UN and led a study of Latin American prison conditions. She didn’t return to Spain until 1977 when she received a gracious welcome. She spent her last years in New York where she died in 1987. In the United States her partner of nearly forty years was philanthropist Louise Crane who earlier had a relationship with the poet Elizabeth Bishop. There’s a college and railway station in Málaga named after Kent.

Photo from Bibioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes

The central Málaga train station is named after the philosopher and essayist María Zambrano who I reported on. Zambrano was born in Málaga province, but her family moved to Madrid several years later and then to Segovia where her father taught Spanish grammar. Her father was a friend and collaborator of the poet Antonio Machado. Zambrano studied under the philosopher José Ortega y Gasset in Madrid and later taught metaphysics at Madrid University. She was a member of the group Las Sinsombrero, a group of female artists and intellectuals who demonstrated their rebellion by taking off their hats in public, a gesture that broke societal norms. Most of them ended up in exile with the end of the Spanish Civil War and the beginning of the Franco era in 1939. Zambrano did not return until 1985, nearly nine years after the death of Franco. In 1988 Zambrano was the first woman to win the Cervantes Prize, which honors the lifetime achievement of a writer in Spanish.

Photo from RTVE.es

Fiona gave us the story of singer/actress Marisol who was discovered at eleven years old by film producer Manual Goyanes. Having convinced her parents to sign an exclusive contract with him, Goyanes essentially controlled her life, resulting years later in accusations of career exploitation and sexual abuse. Marisol’s career spanned twenty-five years, and she gained fame throughout Spain and Latin America. As a Colombian American, Diana can attest to Marisol’s impact. In adulthood, Marisol reverted to her given name Pepa Flores and appeared in Carlos Saura’s Blood Wedding and in Carmen. She was married for four years to the very gorgeous and extremely unfaithful dancer Antonio Gades with whom she had three daughters. She now lives in Málaga, and we have hopes of one day glimpsing her on the street.

It was a lovely afternoon of food, drink, and good company to practice Spanish and learn about notable Spanish mujeres.

PS – We missed our friend Nancy who couldn’t make it to this meeting.