Tour the Hourglass Museum and Cloud Pharmacy

As a prose writer with very little experience with poetry, and, therefore, without the vocabulary to properly reflect on it with any degree of sophistication, I offer some unschooled, gut responses to these lovely new collections of poetry by Kelli Russell Agodon and Susan Rich. I also asked them each a question, to which they kindly responded, offering some insight into their process.

Hourglass Museum (White Pine Press) by Kelli Russell Agodon

Hourglass Museum (White Pine Press) by Kelli Russell Agodon

There’s much to admire about Hourglass Museum, but here’s what I loved most: Kelli Russell Agodon is just charmingly and elegantly clever with words. Hers is not the look-at-me, jokey kind of cleverness, but the kind that emerges seemingly without effort to stun you with its grace and aptness. I read these lines over and over from the poem “Drowning Girl: A Waterlogged Ars Poetica” to savor their sound and substance.

There’s no dessert in the picnic basket/so I swallow time. My mouth full/of hands and numbers. I ask for seconds.

Agodon manages to achieve a playfulness while pulling you under to the poem’s depths. Throughout the book, she mixes melancholy with cheekiness, longing with mock (and, sometimes, real) rebellion.

The book opens with an epigraph by Anais Nin: Reality doesn’t impress me. I only believe in intoxication, in ecstasy and when ordinary life shackles me, I escape, one way or another. There are in these poems, many references to escape. There is mention of exits and entrances, doorways and windows and where they might lead: museums, an unlocked cage, a church, or in “Death of a Housewife, Oil on Linen” an entirely new existence: … what she wanted/was to tango with another or a key/to unlock the front door and waltz/herself into another life.

Agodon also considers how our veneration for our heroes can both inspire and shrink us. In “Frida Kahlo Tattoo,” she writes: I wear a temporary tattoo/of Frida Kahlo believing/I can change the world/and if not the world/then a lightbulb, the channel …

Many of the poems are inspired by paintings, and the reader can almost imagine the poems themselves framed and hanging in a museum. The book has four parts, each dealing with an aspect of work in an exhibition, rendering in words the quirky, keen depths of the poet’s vision. In her prologue poem, Agodon invites the reader to … look up and see the madness/organized in the stars.

Here’s the question (or rather, questions) I asked Kelli Russell Agodon: You have a talent for the comic and the absurd, for puns and other word play, which is such a delightful part of your work. How did that develop? When were you aware of that ability? How does it affect your way of seeing the world?

Here’s Kelli’s response:

I have always seen words a little different from others. Part of that is mild dyslexia and part of that is just how I am wired to visually see the world;  I have always drawn connections between things and sometimes see patterns in both words and images that others may overlook.

I have always drawn connections between things and sometimes see patterns in both words and images that others may overlook.

The earliest I remember this happening with words was being a young girl and my mom saying it was okay for me to go to the restroom by myself in an Italian restaurant. I remember turning the corner and seeing a giant sign that read: “LA DIES!” I remember having my heart jump, what does this mean? Has something happened in California? Of course, what the sign said was “LADIES,” but it wasn’t how I read it.

As a kid, I was always drawn to word games including crossword puzzles, word searches, hours of Boggle and Scrabble with my family; it was just an enjoyable way for me to spend the day playing with letters. I tend to group letters together differently than others, someone may see “marathon” and if asked to break it down, may write “mara-thon,” I may look at the word and see “ma-rat-hon.” I have to correct myself every time I go to pronounce “extraordinary,” because I always just want to say, “extra ordinary.” I know the word, but my mind is constantly regrouping things in words, but also in images, patterns, and visually throughout the day.

I am also someone who will sit and just look at something, whether a word or landscape, for a long time allowing my mind to wander. I think my ability to daydream creates even more of this throughout my life. I am a big believer in downtime and to just be in the world and I think this quiet or daydreaming time allows your mind to wander, sort of like a spider’s web, connecting one thread to the other. For me, these connections also happen in words and letters.

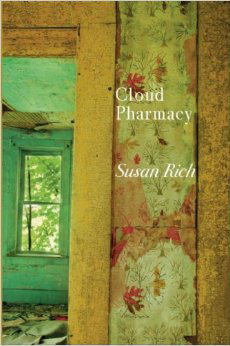

Cloud Pharmacy (White Pine Press) by Susan Rich

Cloud Pharmacy (White Pine Press) by Susan Rich

… don’t let go, let go.

This last line in “The Tangible, Intangible,” one of Susan Rich’s poems inspired by the nineteenth-century photographer Hannah Maynard, captures for me the essence of Cloud Pharmacy, a collection that is intelligent and observant, and which deftly exposes one’s contradictory passions, needs, and even self-regard. Rich addresses several themes in her new book, one of which is grief.

In a section of the book called Dark Room, Rich reflects on the curious and haunting multiple-exposure self-portraits by Maynard, whose daughter died as a teenager. In Rich’s poems, Maynard is a figure that “stands neither in/nor out of the century but floats.” Or, in yet another multiple-exposure, “Hannahs stand here, sit there, bend over …” In another poem, “she overlaps the images and leaves/no line of separation.”

Even in the other poems, the ones on love and fire, there are these opposing perceptions of what is real and what we want to believe. In “There is No Substance That Does Not Carry One Inside of It,” an encroaching fire moves foreigners to politely request action from their Spanish hotelier, who observes the fire, “the little/ flames clearly flirtatious, clearly beyond belief.” Rich creates a sense of the surreal, which pages later she casts off with a straight-on admonition with a letter to the fire, which includes the anxiety-laden question, “Am I wrong even to write?”

In “Conundrum,” the narrator enumerates the dichotomies presented by coupledom, the choices that are available, and the questions that arise only to conclude the inconclusive—that “We are bound/we are cleaving/we are bi.”

The twining in the book of the themes of love, grief and fire, and, within individual poems, the “don’t let go, let go” contradiction create a richly thought-provoking collection of poems.

Here’s the question I asked Susan Rich: You write about grief and love, two emotions that are quite entwined. And then there is the specter of fire, its power to consume life. In the collection, the three themes play off of each other quite effectively. How readily did these three themes coalesce for you as you put together the collection?

Here’s Susan’s response:

I’m really pleased that you discovered these themes as you read through my collection. As you’ve discerned, I am a faithful fan of the braided structure for a poetry collection; in other words, a book where three themes interweave together and (hopefully) gain emotional power as the collection unfolds.  In Cloud Pharmacy, these themes presented early on because they were/are themes prevalent in my life.

In Cloud Pharmacy, these themes presented early on because they were/are themes prevalent in my life.

When I read at Open Books: A Poem Emporium for the book launch earlier this month, I mentioned being caught in wildfires in Spain the summer I turned 50. I’d been invited to an artist residency, Fundación Valparaíso, and in the third week was evacuated to a nearby town, from which we were evacuated again. So the sense of an encroaching fire is very real to me. At times, the flames were far too close to us. In the chaos, I was separated from the main group of artists and took to the road with friends who happened to be visiting me at the time. After several days in transit, I returned to Seattle but the smell of smoke stuck to my skin and clothes for weeks no matter how frequently I washed.

All of this is just to say that the memory of intense fire stayed with me in a very real sense as I wrote these poems. Another life changing event soon after returning from this trip was falling in love; so love and fire joined hands together quite easily. Finally, the section of the book, “Dark Room” concerns the Victorian photographer, Hannah Maynard, one of British Columbia’s first professional photographers. Maynard was a proto-surrealist (who also attended séances at the Mayor’s home) and in the early 1890’s, after the death of her daughter Lily, she created a set of multiple exposure self-portraits; her grief is palpable in these portraits.

I hope that any reader will feel these interconnections, either consciously or unconsciously.