The Art of the Long Walk

When my husband dropped me off at Golden Gardens Park last Thursday for the start of the Long Walk, many of the walkers had already assembled. “That’s not your demographic,” he chuckled. Indeed, many of the participants were decades younger than I. But at 59, I’m quite fit, having been a runner for over 30 years and a frequent biker. And with the theft of our car seven months ago, traveling on foot has become somewhat routine. My physical readiness for the walk wasn’t in doubt.

The question was how open was I to the social aspect of walking with strangers, to what extent could I, inveterate introvert, become part of this improvised community. When I was much younger and needier, the question might have been one born out of a preoccupation with self: Would anyone like me? At this stage of my life, the question was less egotistical: What would be my relevance to and understanding of this group, to the spaces I would traverse and occupy, and, because this was an arts project, to the notion of art beyond the tangible thing that is drawn or shaped with the hands, made permanent on paper or hung on a wall.

The Long Walk is a four-day, forty-five mile walk from Puget Sound to Snoqualmie Falls using the King County Regional Trails System. It was conceived by artist Susan Robb as an experiential event in which 50 people walk out of the city through farmland and into forest. Participants are encouraged to view their experiences as art.

Some of those experiences were within the familiar realm of visual, performing, and literary arts. There were the blue trees we passed on the Burke-Gilman Trail in Kenmore, part of Australian artist Konstantin Dimopoulos’s international art installation meant to draw attention to deforestation. There was the delightful Snoqualmie Floodplain Cabaret that entertained us with songs and skits at McCormick Park, our mid-point campsite in Duvall. There were the poems that Eugene, OR poet Michelle Peñaloza read each morning that reflected in some way the landscape we would encounter that day, and there were the prompts she provided to inspire a poem of our own making.

Some of those experiences were within the familiar realm of visual, performing, and literary arts. There were the blue trees we passed on the Burke-Gilman Trail in Kenmore, part of Australian artist Konstantin Dimopoulos’s international art installation meant to draw attention to deforestation. There was the delightful Snoqualmie Floodplain Cabaret that entertained us with songs and skits at McCormick Park, our mid-point campsite in Duvall. There were the poems that Eugene, OR poet Michelle Peñaloza read each morning that reflected in some way the landscape we would encounter that day, and there were the prompts she provided to inspire a poem of our own making.

Beyond these and the other examples of art as performance or product we were treated to, there were the instances of art as a process or experience.

An activity on the first day consisted of individuals expressing a need (a pencil, an indoor swing, a job ) to which anyone able to meet that need could respond by filling out a form in triplicate, with copies being distributed to the need expresser, the need fulfiller, and Susan. The art was in the ironic combination of the bureaucratic triplicate form and the social reciprocity of the exercise, a connecting of human beings to one another.

Picking raspberries and fava beans at Oxbow Organic Farm offered artistic engagement not only in the act of writing love notes from the point of view of the produce to the eventual consumer at the Ballard Farmers Market, but in the act of picking itself: the tactile sensation of separating fruit from stalk, the visual pleasure of the accumulated berries and beans in baskets, the satisfaction of contributing to the transport of crop to table.

Picking raspberries and fava beans at Oxbow Organic Farm offered artistic engagement not only in the act of writing love notes from the point of view of the produce to the eventual consumer at the Ballard Farmers Market, but in the act of picking itself: the tactile sensation of separating fruit from stalk, the visual pleasure of the accumulated berries and beans in baskets, the satisfaction of contributing to the transport of crop to table.

And on the subject of transport, there was the party bus that awaited us after the vigorous trudge up and down the hills of the Tolt Pipeline Trail. The absurdity of a bus equipped with a dancer pole and disco laser lights was made more perfectly absurd when our band of sweat-soaked walkers occupied it.

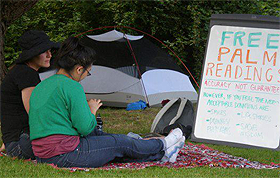

As part of her project An Excuse to Hold Your Hand, artist Joyce Wong read our palms. She held our hand, the left if we wanted to know the potential we had been born with and the right if we wanted to know what we had realized or accumulated in our life. She read my left hand and told me there was something missing in my life. A once-true statement. If she had read my right hand, she might have seen that the missing something had been addressed when twenty years ago I turned to art, beginning the long, self-directed apprenticeship of writing fiction—a pursuit that filled my need for expression, story, and solitude.

As part of her project An Excuse to Hold Your Hand, artist Joyce Wong read our palms. She held our hand, the left if we wanted to know the potential we had been born with and the right if we wanted to know what we had realized or accumulated in our life. She read my left hand and told me there was something missing in my life. A once-true statement. If she had read my right hand, she might have seen that the missing something had been addressed when twenty years ago I turned to art, beginning the long, self-directed apprenticeship of writing fiction—a pursuit that filled my need for expression, story, and solitude.

I’m quiet. I disappear in large groups, my voice inaudible and my demeanor diffident as I hug the periphery or hide amid the swirl. But I do like to engage with others one-to-one or in small groups. I regret I never got around to meeting everyone in the group of fifty walkers. I like walking fast so I tended to fall in with those of a similar pace, among them the dancer and aerialist with the lithe body and enviable triceps; the breast cancer research scientist whose willowy frame and flowing attire conjured a woodland enchantress; the young biology major and pre-med student whose vision it is to open a community-supported hospital that delivers affordable care to all of its members; the brothers who last year walked the 500 miles of the proposed high speed rail route from Los Angeles to San Francisco to explore the struggle between personal and emotional ties to the land and the utilitarian benefits of a major public works project. I extend my gratitude to them and all the others—artists, environmentalists, scientists, dreamers, and doers—with whom I had the pleasure of walking a common path for four art-filled days.

I’m quiet. I disappear in large groups, my voice inaudible and my demeanor diffident as I hug the periphery or hide amid the swirl. But I do like to engage with others one-to-one or in small groups. I regret I never got around to meeting everyone in the group of fifty walkers. I like walking fast so I tended to fall in with those of a similar pace, among them the dancer and aerialist with the lithe body and enviable triceps; the breast cancer research scientist whose willowy frame and flowing attire conjured a woodland enchantress; the young biology major and pre-med student whose vision it is to open a community-supported hospital that delivers affordable care to all of its members; the brothers who last year walked the 500 miles of the proposed high speed rail route from Los Angeles to San Francisco to explore the struggle between personal and emotional ties to the land and the utilitarian benefits of a major public works project. I extend my gratitude to them and all the others—artists, environmentalists, scientists, dreamers, and doers—with whom I had the pleasure of walking a common path for four art-filled days.

Thanks to Elise Fogel for her photo of Joyce Wong and to Mark Lewin for the other photos in this post.